- Marginal farmers, 41% of total, operate only 11% land

- Approximately 40% of farm households are pure landless tenant

- Only 23% of farmers receive agricultural extension service support

Although the British-era Zamindari system was abolished long ago through the East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950 (commonly known as the Zamindari Abolition Act), significant disparities in land ownership persist in modern-day Bangladesh.

A large proportion of farmers in Bangladesh do not own any land, which impedes the potential for further growth in the agricultural sector—a critical component of the country’s economy, where the sector alone employs over 40% of the working population.

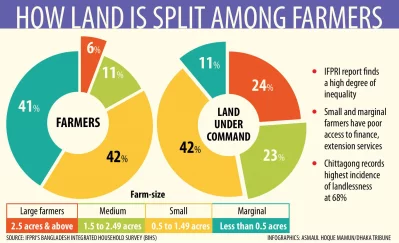

A recently published report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) highlights a high degree of inequality in the distribution of arable land. According to the report, marginal farmers, who represent 41% of all farmers, operate only 11% of the land, whereas the 6% of large farmers control a quarter of the country's arable land.

Land remains crucial for agricultural production, yet 56% of rural households in Bangladesh are landless, states IFPRI in its report titled Food Security and Nutrition in Bangladesh: Evidence-based Strategies for Advancement, co-authored by Akhter U Ahmed, M Mehrab Bakhtiar, and Moogdho M Mahzab.

The incidence of landlessness varies significantly across regions, ranging from 47% in Khulna Division to 68% in Chittagong Division.

The Washington-based global food policy think tank, IFPRI, observes that the overwhelming majority of small and marginal farmers in Bangladesh are unable to make substantial investments due to their disadvantaged position. They face limited access to formal banking credit and official agricultural extension services.

In Bangladesh, the distribution of arable land is highly unequal. Large and medium farmers, who constitute only 17% of the country’s farming population, operate nearly half (47%) of the arable land, while the remaining 83%—small and marginal farmers—cultivate the other half (53%).

Among those who own cultivable land, the bottom 25% of households own just 3.8% of the total cultivable land. In stark contrast, the top 5% of households own 26.4%, and the top 10% control 39.7% of all cultivable land in rural Bangladesh.

A large proportion of farmers do not own any land

Approximately 40% of all farm households are pure tenants, meaning they do not own the land they cultivate.

About 36% of farmers cultivate only their own land.

The proportion of mixed-tenant farmers—those who cultivate both their own land and rented land (as sharecroppers and/or leaseholders)—is 23%.

The dominant land-tenure arrangement is sharecropping, in which the crops produced are shared between the cultivator and the landowner in agreed-upon proportions prior to cultivation.

Approximately 43% of farmers are sharecroppers (28% pure tenants and 15% mixed tenants), while about 16% of farmers have cash-lease arrangements (10% pure tenants and 6% mixed tenants).

Chittagong and Sylhet divisions have the highest percentages of pure tenants, at 50% and 47%, respectively.

Access to finance limited, specially for smallholder farmers

Access to finance is essential for farmers to invest in productive resources, enhance agricultural productivity, and build resilience against economic shocks.

However, financial access remains limited, particularly for smallholder farmers, who face significant challenges in obtaining formal financing from banks.

As a result, many farmers resort to higher-cost credit sources, such as microfinance institutions and nongovernmental organizations, as well as informal lenders, including local moneylenders, family, and friends. These alternatives often involve higher interest rates and less favorable repayment terms.

In Bangladesh, where smallholder farmers make up the majority, increasing their incomes is crucial for achieving broader poverty reduction goals.

Due to their limited access to land, smallholder farmers rely heavily on the production of high-value crops, such as horticulture, to boost their incomes.

Adequate access to institutional credit and effective agricultural extension services is vital for supporting these farmers. Access to finance enables them to invest in productive resources, improve agricultural productivity, and mitigate the impacts of economic shocks.

Currently, financial access is significantly constrained, particularly for smallholder farmers. For example, in 2022, 81.4% of marginal farmers and 78.3% of smallholders relied on microfinance institutions and nongovernmental organizations for financing, while only 2.7% and 5.3%, respectively, accessed loans from banks. These figures highlight the limited reach of formal banking services in rural areas.

Although microfinance loans often come with higher interest rates, their faster disbursement and simpler documentation processes make them attractive to farmers.

The continued reliance on informal credit sources underscores the inadequacy of formal credit channels in supporting productivity improvements.

Addressing this challenge requires innovative financing models, such as post-harvest loan repayment schemes, to overcome collateral-related barriers.

Limited access to agricultural extension hinders development

Agricultural extension services play a pivotal role in empowering farmers by providing essential knowledge, skills, and techniques to enhance their agricultural practices.

An IFPRI report finds that many farmers in Bangladesh, especially smallholders, lack access to such support.

Instead, they often rely on informal networks, learning about new technologies and practices through peer-to-peer exchanges rather than from extension officials.

Although marginal and small-scale farmers constitute the largest share of farmers in Bangladesh, their contact with agricultural extension officials is very low and significantly less than that of medium- and large-scale farmers.

Overall, about 23% of farmers received extension services. While 38% of large-scale farmers accessed extension services, only 16% of marginal farmers benefited from them.

More vulnerable to climate shocks

Climate change has varying effects on key populations and geographic regions. IFPRI’s research in Bangladesh shows that it disproportionately impacts the rural poor, who have the least capacity to adapt to its effects.

Evidence indicates that smallholder farmers, compared to large-scale farmers, are more vulnerable to environmental degradation and the impacts of climate change due to their limited access to resources such as human, social, and financial capital, as well as information.

Farmers exposed to climate-induced shocks are less likely to adopt stress-tolerant technologies, especially smallholder farmers and sharecroppers.

This article was originally published on December 26, 2024 in Dhaka Tribune. This article refers to IFPRI's food security assessment report, which can be downloaded here.